Richard Cromwell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last

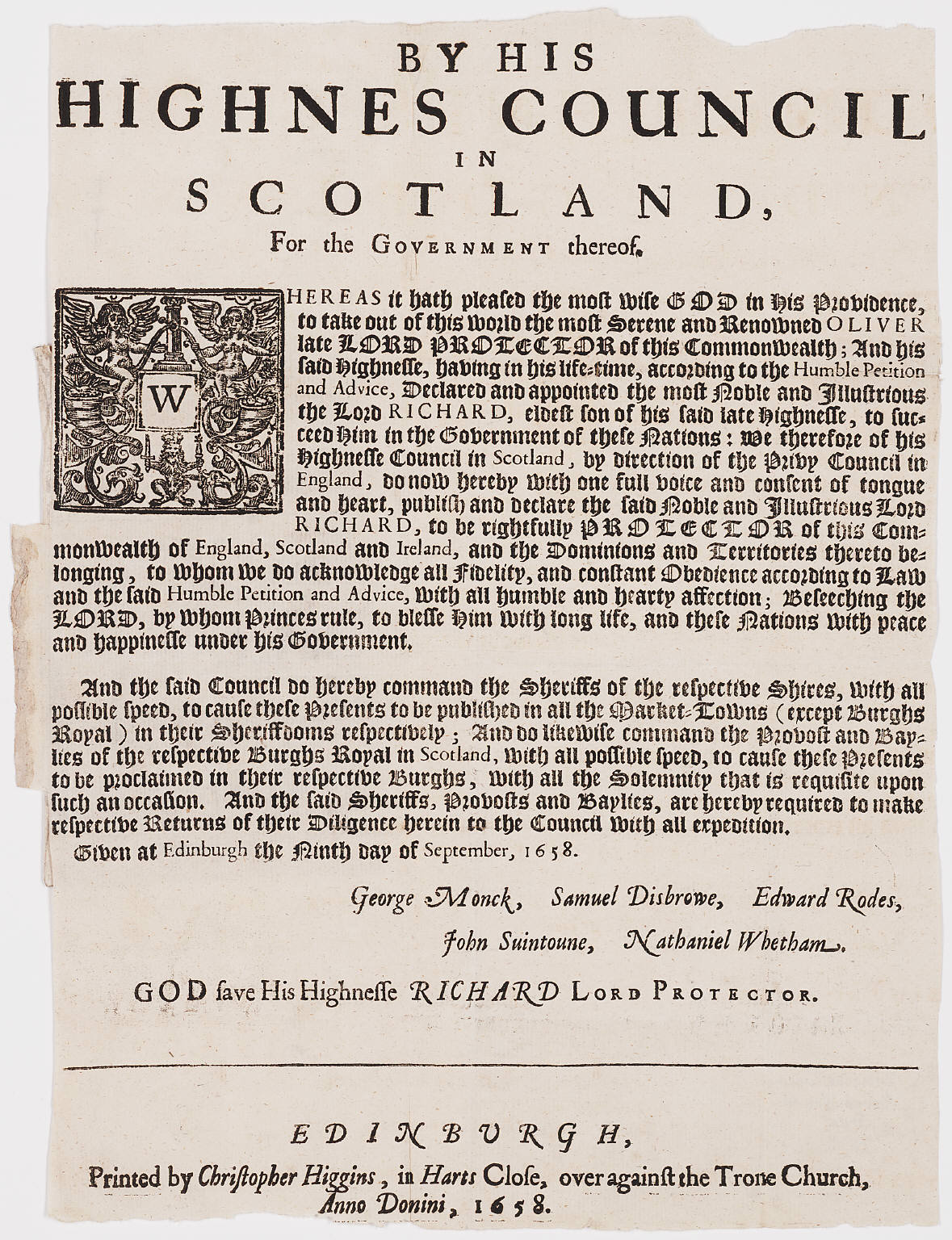

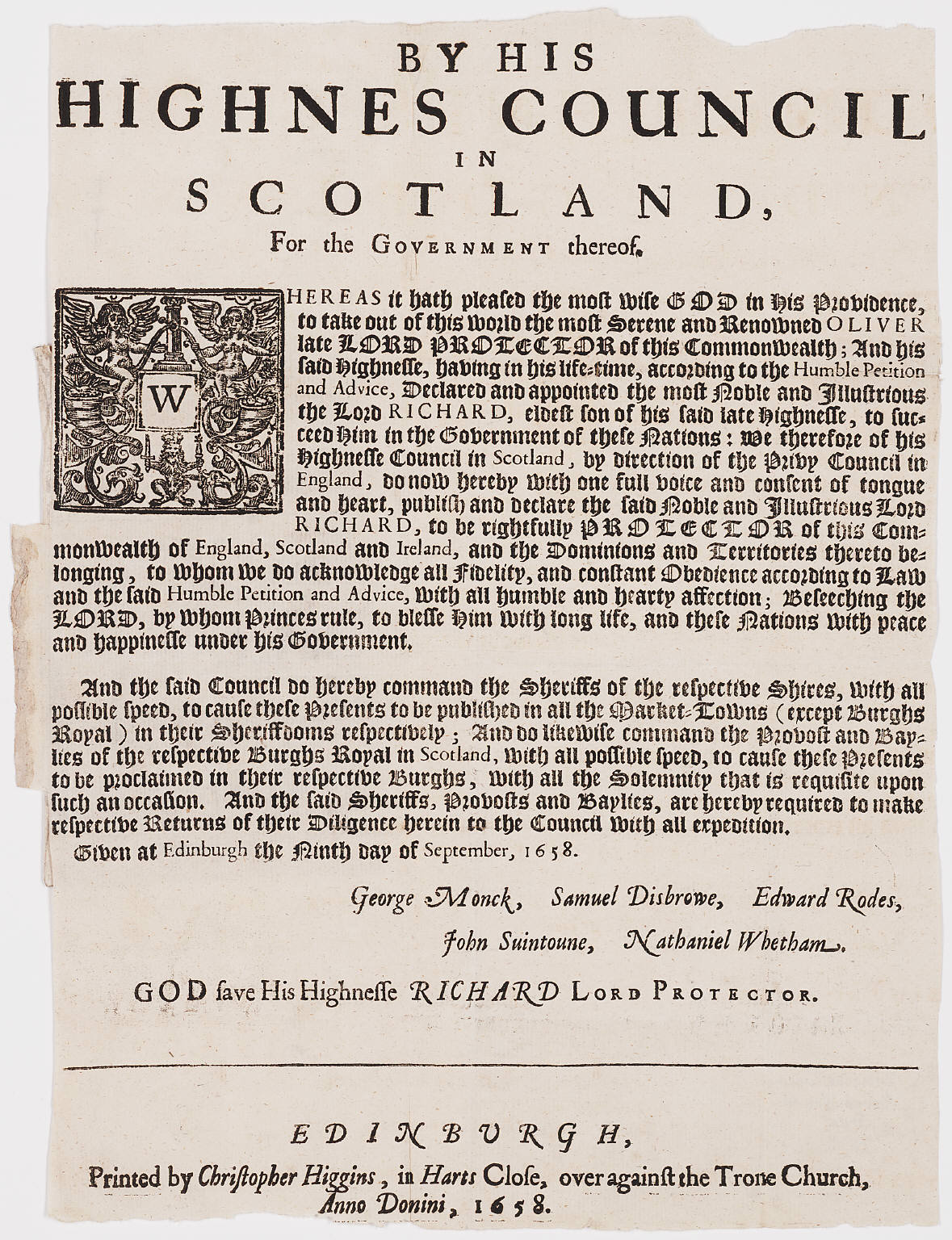

Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, and Richard was informed on the same day that he was to succeed him. Some controversy surrounds the succession. A letter by

Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, and Richard was informed on the same day that he was to succeed him. Some controversy surrounds the succession. A letter by  At the same time, the officers of the New Model Army became increasingly wary about the government's commitment to the military cause. The fact that Cromwell lacked military credentials grated with men who had fought on the battlefields of the English Civil War to secure their nation's liberties. Moreover, the new Parliament seemed to show a lack of respect for the army which many military men found alarming. In particular, there were fears that Parliament would make military cuts to reduce costs, and by April 1659 the army's general council of officers had met to demand higher taxation to fund the regime's costs.

Their grievances were expressed in a petition to Cromwell on 6 April 1659 which he forwarded to the Parliament two days later. Yet Parliament did not act on the army's suggestions; instead they shelved this petition and increased the suspicion of the military by bringing articles of impeachment against

At the same time, the officers of the New Model Army became increasingly wary about the government's commitment to the military cause. The fact that Cromwell lacked military credentials grated with men who had fought on the battlefields of the English Civil War to secure their nation's liberties. Moreover, the new Parliament seemed to show a lack of respect for the army which many military men found alarming. In particular, there were fears that Parliament would make military cuts to reduce costs, and by April 1659 the army's general council of officers had met to demand higher taxation to fund the regime's costs.

Their grievances were expressed in a petition to Cromwell on 6 April 1659 which he forwarded to the Parliament two days later. Yet Parliament did not act on the army's suggestions; instead they shelved this petition and increased the suspicion of the military by bringing articles of impeachment against

BBC Bio of Oliver Cromwell

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cromwell, Richard 1626 births 1712 deaths 17th-century English politicians 18th-century English people 17th-century English judges Members of the pre-1707 Parliament of England for the University of Cambridge Heads of state of England People educated at Felsted School New Model Army personnel Chancellors of the University of Oxford People from Huntingdon Republicanism in England

Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

.

On his father's death in 1658 Richard became Lord Protector, but lacked authority. He tried to mediate between the army and civil society and allowed a Parliament containing many disaffected Presbyterians and Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

s to sit. Suspicions that civilian councillors were intent on supplanting the army were brought to a head by an attempt to prosecute a major-general for actions against a Royalist. The army made a threatening show of force against Richard and may have had him in detention. He formally renounced power nine months after succeeding.

Although a Royalist revolt was crushed by the recalled civil war figure General John Lambert John Lambert may refer to:

*John Lambert (martyr) (died 1538), English Protestant martyred during the reign of Henry VIII

*John Lambert (general) (1619–1684), Parliamentary general in the English Civil War

*John Lambert of Creg Clare (''fl.'' c. ...

, who then prevented the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" n ...

from reconvening and created a Committee of Safety, Lambert found his troops melted away in the face of General George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

's advance from Scotland. Monck then presided over the Restoration of 1660

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to be ...

. Cromwell went into exile on the Continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

, and lived in relative obscurity for the remainder of his life. He eventually returned to his English estate and died in his eighties. He has no living descendants.

Early years and family

Cromwell was born in Huntingdon on 4 October 1626, the third son of Oliver Cromwell and his wifeElizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

. Little is known of his childhood. He and his three brothers were educated at Felsted School

(Keep your Faith)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent day and boarding

, religion = Church of England

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Chris Townsend

, r_head_l ...

in Essex close to their mother's family home. There is no record of his attending university. In May 1647, he became a member of Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincoln ...

, however he was not called to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

subsequently. Instead, in 1647 Cromwell joined the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

as a captain in Viscount Lisle

The title of Viscount Lisle has been created six times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, on 30 October 1451, was for John Talbot, 1st Baron Lisle. Upon the death of his son Thomas at the Battle of Nibley Green in 1470, the viscount ...

's lifeguard

A lifeguard is a rescuer who supervises the safety and rescue of swimmers, surfers, and other water sports participants such as in a swimming pool, water park, beach, spa, river and lake. Lifeguards are trained in swimming and CPR/ AED first a ...

, and later that year was appointed captain in Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

's lifeguard.

In 1649 Cromwell married Dorothy Maijor, daughter of Richard Maijor

Richard Major or Richard Maijor (1605 – 25 April 1660) was a Member of Parliament during the English Commonwealth era.

Major was the son of John Maijor, Alderman and Mayor of Southampton. He bought Hursley Park and Lodge, Hampshire in 1639 ...

, a member of the Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

gentry. He and his wife then moved to Maijor's estate at Hursley

Hursley is a village and civil parish in Hampshire, England with a population of around 900 in 2011. It is located roughly midway between Romsey and Winchester on the A3090. Besides the village the parish includes the hamlets of Standon and ...

in Hampshire. During the 1650s they had nine children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Cromwell was named a Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

for Hampshire and sat on various county committees. During this period Richard seems to have been a source of concern for his father, who wrote to Richard Maijor saying, "I would have him mind and understand business, read a little history, study the mathematics and cosmography

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-scal ...

: these are good, with subordination to the things of God. Better than idleness, or mere outward worldly contents. These fit for public services, for which a man is born".

Political background

Oliver Cromwell had risen from being an unknown member of Parliament in his forties to being a commander of the New Model Army, which emerged victorious from theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. When he returned from a final campaign in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell became disillusioned at inconclusive debates in the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" n ...

between Presbyterians and other schools of thought within Protestantism. Parliamentarian suspicion of anything smacking of Catholicism, which was strongly associated with the Royalist side in the war, led to enforcement of religious precepts that left moderate Anglicans barely tolerated.

A Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

regime strictly enforced the Sabbath, and banned almost all form of public celebration, even at Christmas. Cromwell attempted to reform the government through an army-nominated assembly known as Barebone's Parliament

Barebone's Parliament, also known as the Little Parliament, the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints, came into being on 4 July 1653, and was the last attempt of the English Commonwealth to find a stable political form before the inst ...

, but the proposals were so unworkably radical that he was forced to end the experiment after a few months. Thereafter, a written constitution created the position of Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

for Cromwell and from 1653 until his death in 1658, he ruled with all the powers of a monarch, while Richard took on the role of heir.

Move into political life

In 1653, Richard Cromwell was passed over as a member of Barebone's Parliament, although his younger brotherHenry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

was a member of it. Neither was he given any public role when his father was made Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

in the same year; however, he was elected to the First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the Hou ...

as M.P. for Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver Cromwell was born there ...

and the Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first session, the House of Commons was its only chamber; in t ...

as M.P. for Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Under the Protectorate's constitution, Oliver Cromwell was required to nominate a successor, and from 1657 he involved Richard much more heavily in the politics of the regime. He was present at the second installation of his father as Lord Protector in June, having played no part in the first installation. In July he was appointed chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

of Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and in December was made a member of the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.

Lord Protector (1658–59)

Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, and Richard was informed on the same day that he was to succeed him. Some controversy surrounds the succession. A letter by

Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, and Richard was informed on the same day that he was to succeed him. Some controversy surrounds the succession. A letter by John Thurloe

John Thurloe (June 1616 – 21 February 1668) was an English politician who served as secretary to the council of state in Protectorate England and spymaster for Oliver Cromwell and held the position of Postmaster General between 1655 and 1660. ...

suggests that Cromwell nominated his son orally on 30 August, but other theories claim either that he nominated no successor, or that he put forward Charles Fleetwood

Charles Fleetwood (c. 1618 – 4 October 1692) was an English Parliamentarian soldier and politician, Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1652–1655, where he enforced the Cromwellian Settlement. Named Cromwell's Lieutenant General for the Third Englis ...

, his son-in-law.

Richard was faced by two immediate problems. The first was the army, which questioned his position as commander given his lack of military experience. The second was the financial position of the regime, with a debt estimated at £2 million. As a result, Cromwell's Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

decided to call a parliament in order to redress these financial problems on 29 November 1658 (a decision which was formally confirmed on 3 December 1658). Under the terms of the Humble Petition and Advice

The Humble Petition and Advice was the second and last codified constitution of England after the Instrument of Government.

On 23 February 1657, during a sitting of the Second Protectorate Parliament, Sir Christopher Packe (politician), Christop ...

, this Parliament was called using the traditional franchise (thus moving away from the system under the Instrument of Government

The Instrument of Government was a constitution of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. Drafted by Major-General John Lambert in 1653, it was the first sovereign codified and written constitution in England.

Antecedence

The '' ...

whereby representation of rotten boroughs

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electora ...

was cut in favour of county town

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, a county town is the most important town or city in a county. It is usually the location of administrative or judicial functions within a county and the place where the county's members of Parliament are elect ...

s). This meant that the government was less able to control elections and therefore unable to manage the parliament effectively. As a result, when this Third Protectorate Parliament

The Third Protectorate Parliament sat for one session, from 27 January 1659 until 22 April 1659, with Chaloner Chute and Thomas Bampfylde as the Speakers of the House of Commons. It was a bicameral Parliament, with an Upper House having a powe ...

first sat on 27 January 1659 it was dominated by moderate Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, crypto-royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

s and a small number of vociferous Commonwealthsmen (or Republicans).

The "Other House" of Parliament – a body which had been set up under the Humble Petition and Advice to act as a balance on the Commons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

– was also revived. It was this second parliamentary chamber and its resemblance to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

(which had been abolished in 1649) that dominated this Parliamentary session. Republican malcontents gave filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

ing speeches about the inadequacy of the membership of this upper chamber (especially its military contingent) and also questioned whether it was indicative of the backsliding of the Protectorate regime in general and its divergence from the "Good Old Cause

The Good Old Cause was the name given, retrospectively, by the soldiers of the New Model Army, to the complex of reasons that motivated their fight on behalf of the Parliament of England.

Their struggle was against King Charles I and the Royalis ...

" for which parliamentarians had originally engaged in civil war. Reviving this House of Lords in all but name, they argued, was but a short step to returning to the Ancient Constitution The ancient constitution of England was a 17th-century political theory about the common law, and the antiquity of the House of Commons, used at the time in particular to oppose the royal prerogative. It was developed initially by Sir Edward Coke, i ...

of King, Lords and Commons.

William Boteler

William Boteler (''fl.'' 1640s and 1650s) was a member of the Parliament of England. After the English Civil War, he was appointed Major-General for Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire, Northamptonshire and Rutland during the Rule of the Major-General ...

on 12 April 1659, who was alleged to have mistreated a royalist prisoner while acting as a major-general under Oliver Cromwell in 1655. This was followed by two resolutions in the Commons on 18 April 1659 which stated that no more meetings of army officers should take place without the express permission of both the Lord Protector and Parliament, and that all officers should swear an oath that they would not subvert the sitting of Parliament by force.

These direct affronts to military prestige were too much for the army grandees to bear and set in motion the final split between the civilian-dominated Parliament and the army, which would culminate in the dissolution of Parliament and Cromwell's ultimate fall from power. When Cromwell refused a demand by the army to dissolve Parliament, troops were assembled at St. James's Palace. Cromwell eventually gave in to their demands and on 22 April, Parliament was dissolved and the Rump Parliament recalled on 7 May 1659.

In the subsequent month, Cromwell did not resist and refused an offer of armed assistance from the French ambassador, although it is possible he was being kept under house arrest by the army. On 25 May, after the Rump agreed to pay his debts and provide a pension, Cromwell delivered a formal letter resigning the position of Lord Protector. "Richard was never formally deposed or arrested, but allowed to fade away. The Protectorate was treated as having been from the first a mere usurpation."

He continued to live in the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

until July, when he was forced by the Rump to return to Hursley. Royalists rejoiced at Cromwell's fall, and many satirical attacks surfaced, in which he was given the unflattering nicknames "Tumbledown Dick" and "Queen Dick".Fraser, Antonia (1979). ''King Charles II''. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 163.

Dates as Lord Protector

* 3 September 1658 – 25 May 1659. Title: ''His Most Serene Highness'' By the Grace of God, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and the Dominions thereunto belonging.Later years (1659–1712)

During the political difficulties of the winter of 1659, there were rumours that Cromwell was to be recalled as Protector, but these came to nothing. In July 1660, Cromwell left for France, never to see his wife again. While there, he went by a variety of pseudonyms, including John Clarke. He later travelled around Europe, visiting various European courts. As a visiting Englishman, he was once invited to dine withArmand de Bourbon, Prince of Conti

Armand de Bourbon, Prince of Conti (11 October 162926 February 1666), was a French nobleman, the younger son of Henri II, Prince of Condé and Charlotte Marguerite de Montmorency, daughter of Henri I, Duke of Montmorency. He was the brother of ...

, who was unaware of who he was. At dinner, the prince questioned Cromwell about affairs in England and observed, "Well, that Oliver, tho' he was a traitor and a villain, was a brave man, had great parts, great courage, and was worthy to command; but that Richard, that coxcomb and poltroon

Poltroon was an event horse ridden by American rider Torrance Watkins

Torrance Watkins (born July 30, 1949) is an American equestrian and Olympic champion. Formerly known as Torrance Fleischmann, she won a team gold medal in eventing at ...

, was surely the basest fellow alive; what is become of that fool?" Cromwell replied, "He was betrayed by those he most trusted, and who had been most obliged by his father". Cromwell departed from the town the following morning. During this period of voluntary exile, he wrote many letters to his family back in England; these letters are now held by Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies

Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies Service (CALS) is a UK local government institution which collects and preserves archives, other historical documents and printed material relating to the modern county of Cambridgeshire, which includes th ...

at the County Record Office in Huntingdon.

In 1680 or 1681, he returned to England and lodged with the merchant Thomas Pengelly in Cheshunt

Cheshunt ( ) is a town in Hertfordshire, England, north of London on the River Lea and Lee Navigation. It contains a section of the Lee Valley Park, including much of the River Lee Country Park. To the north lies Broxbourne and Wormley, Hertfor ...

in Hertfordshire, living off the income from his estate in Hursley. He died on 12 July 1712 at the age of 85. His body was returned to Hursley and interred in a vault beneath All Saints' Parish Church, where a memorial tablet to him has been placed in recent years. He was the longest-lived British head of state for three centuries, exceeding even the long-lived and far longer reigning George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

, until Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

displaced him at 85 years, 9 months and 9 days in January 2012.

Fictional portrayals

Cromwell has been depicted in historical films. They include ''Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

'' (1970), where he was portrayed by Anthony May, and ''To Kill a King

''To Kill a King'' is a 2003 English Civil War film directed by Mike Barker, and starring Tim Roth, Rupert Everett and Dougray Scott. It centres on the relationship between Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Fairfax in the post-war period from 1648 unt ...

'' (2003), where he was played by John-Paul Macleod.

Cromwell is portrayed in the novel '' The Last Protector'' by Andrew Taylor Andrew or Andy Taylor may refer to:

Sport

* Andrew Taylor (footballer, born 1986), English footballer

* Andy Taylor (footballer, born 1986), English footballer

* Andy Taylor (footballer, born 1988), English footballer

* Andrew Taylor (Australian ...

.

References

Citations

Sources

* *Further reading

* * * * *External links

BBC Bio of Oliver Cromwell

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cromwell, Richard 1626 births 1712 deaths 17th-century English politicians 18th-century English people 17th-century English judges Members of the pre-1707 Parliament of England for the University of Cambridge Heads of state of England People educated at Felsted School New Model Army personnel Chancellors of the University of Oxford People from Huntingdon Republicanism in England

Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

People of the Interregnum (England)

English MPs 1654–1655

English MPs 1656–1658

Lords Protector of England

English justices of the peace

Children of Oliver Cromwell

Man in the Iron Mask